We hear a lot of stories here at Rebels at Work.

Many people are angry at not being heard. Some are sad that their organizations are on a bad downward spiral, with management rallying around what no longer works. Others have checked out of work and checked into being complacent and “just getting the paycheck.”

We hear a lot of stories here at Rebels at Work.

Many people are angry at not being heard. Some are sad that their organizations are on a bad downward spiral, with management rallying around what no longer works. Others have checked out of work and checked into being complacent and “just getting the paycheck.”

For a while the complacent ones got to me the most. To go to work every day and not give a rat’s ass just seems like giving up on life itself.

And the cynicism? Scorching. It would be tough to work with someone with that kind of negative mindset.

But the stories that get to me the most are the people who don’t try to change anything because of the CHANGE MYTH. These people believe that if you’re going to try to fix problems you need to be some sort of crusading take-no-prisoners, storm the ramparts hero.

You might imagine the type. A confident Steve Jobs wannabe talking about disruption, not backing down, go big or go home. The kind of person who doesn’t worry about failing, whether that means getting fired or quitting to find the next gig.

How did this change maker myth become so ingrained in our culture?

Has the Silicon Valley “failure is good” entrepreneurial spirit been taken as “the” way things work at work? Are people with good ideas becoming intimidated about stepping up because they are not Steve Jobs wannabes and they are afraid to fail and lose their jobs?

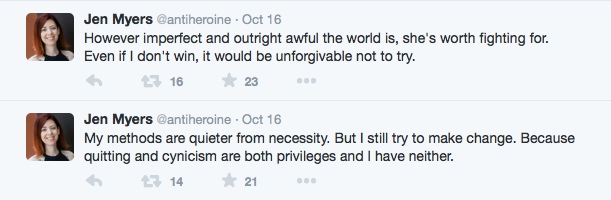

Last week Jen Meyers sent these two tweets that acknowledged the myth and, more importantly, acknowledged the fact that most people making change are doing so thoughtfully within the rules and corporate culture.

Because that’s how so much change happens. Bit by bit. Working with our co-workers vs. leaping from tall buildings in superhero change-maker capes.

If you’re a disruptor and get fired, your big idea dies. So much for heroism.

Whereas if you get smarter about working within the existing organizational culture, your idea actually has a better chance of happening. And you have a better chance of keeping your job.

(Because if we’re honest like Jen, we know that most of us can’t afford to walk away from our jobs. It’s not that simple.)

So maybe it’s useful to remember that having a good idea is easy. Being able to work with people willing to do the hard work to shepherd that idea through corporate politics, budget conflicts, and the often-messy rollout is a privilege.