Stay in the swamp

People are fleeing the swamp of synthesis – that terrible, magical, challenging place where we birth new ideas. It is a swamp filled with discomfort where we look at our research and the hundreds of Post-It notes on the wall and search for patterns and insights that lead us to the “aha” solution.

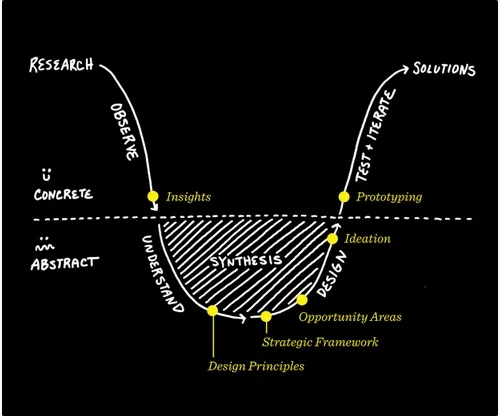

In IDEO’s project “mood map” this is the synthesis phase. And as depicted in the map, it is where our spirits are the lowest. This is the hard, hard work of design and problem solving.

And because it is so difficult, many of us rush through it. We want to get out of the discomfort of ambiguity and uncertainty – and the feeling that we may never get it right.

Is this why we “fail fast”?

When we rush this phase and the initiative turns our mediocre or a bust, we have logical reasons to justify the “fail.” Not enough budget for research. Unrealistic deadlines. Customers aren’t ready for that much innovation.

The most popular and ridiculous excuse is putting on the badge of honor of “failing fast.”

I speak at conferences around the world and this year it seems as though every speaker is urging people to fail fast. Aside from this meme starting to sound trite, I have a hunch that a lot of the fast failing is because we spend too little time in the swamp of synthesis.

The beloved Buddhist monk, teacher and peace activist Thich Nhat Hanh has famously written that “suffering is a kind of mud to help the lotus flower of happiness grow. There can be no lotus flower without the mud.”

Similarly, suffering through the synthesis phase of ideation is necessary to grow our ideas. There can be no innovative ideas without wading through the mud in the synthesis swamp.

How long to slog, when to get out?

But how do you stay in the swamp long enough, despite the discomfort, and how do you know when it’s time to get out? I have no definitive answers here, only observations from facilitating creative teams and doing my own creative work.

First, it’s important that leaders understand the importance of the synthesis swamp and that they need to allow time for this phase. Most are too impatient.

A CEO once said her company hired me for “creativity on demand.” At first, I was honored by the compliment, but then I realized why the company’s people were so frustrated and exhausted. Creativity on demand is not sustainable, nor is it sufficient for complex problem solving.

Perhaps we need to educate executives on what to expect. Maybe it’s a 30/40/30 model: 30 percent research, 40 percent in the swamp, and 30 percent testing.

My personal challenge when I’m lost in the swamp is beating myself up. “I’m not creative enough. I take on projects that are impossible. Maybe I’m just getting too old for work this intense.” You get the gist.

Borrowing advice from Jill Bolte Taylor, author of My Stroke of Insight, I speak to my brain as though it’s a group of children, and tell them, “Stop it. You’re making a racket and not being helpful at all. Whining solves nothing.” A little self-compassion and shutting down the “whining children brain” helps me think clearly.

With that clarity, I ask questions like:

· Are we trying to solve the right problem?

· Asking the right questions?

· Looking at the right research? (Often there’s too much.)

· Have the right people in the swamp with us? (Groupthink often blinds our ability to fully see.)

Call your wild pack

I also call people in my wild pack, those friends and colleagues who are what Adam Grant calls “the disagreeable givers.” They interrogate my thinking, challenge my assumptions and ask difficult questions that jolt me out of my critical thinking and creative rut.

Like the synthesis swamp, these wild pack friends make me uncomfortable. And they are invaluable because the stretch my thinking, point out sloppy work, and dare us to take different approaches.

Most of us have plenty of colleagues in our support pack -- people with compassion and kindness urging us on – and not enough in our wild pack.

When I was writing my first book I asked a well-known author and brilliant and cantankerous consultant to read the first draft. I was in the swamp and knew something was off. He told me that the first two chapters were so boring and ridiculous that he frankly couldn’t stomach reading any more.

I was crushed. And he had done me such a favor. The book eventually won awards, but it could have been a disaster if I had rushed the manuscript to completion.

Document your time in the swamp

My final observation is to write about your time in the swamp after you’ve once again emerged from wading through the mud, self-doubt and frustration, and developed an excellent new idea.

What helped you stay in it? Who and what helped you get through it? How and when did the “aha” s emerge? Keep these notes so you can refer to them the next time you’re in that synthesis phase.

And when you’re really stuck, try to extend the deadline, turn everything off, go for long walks, and have your support pack give you a little TLC.

No mud, no lotus.